0

At our Columbus demonstration on August 13, Kamo-sensei introduced us to something many of our students had never seen before: a Rimpa-cho arrangement. Spanning two containers, the design featured chrysanthemums, stargazer lilies, red maple, and monte casino, woven together with dramatic dried weeping mulberry branches that had been painted metallic gold. Kamo-sensei brought those shimmering branches with him from Japan, and they became the unifying thread of the composition.

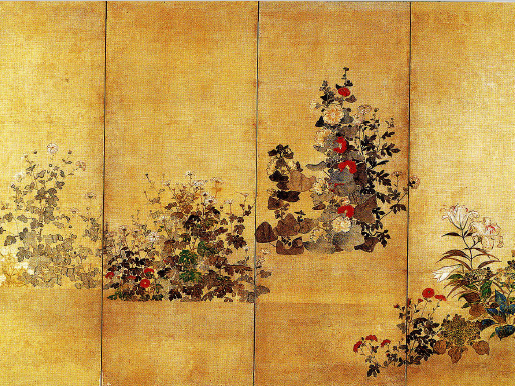

Rimpa (sometimes written Rinpa) is a style of Japanese painting that flourished in the 17th century, led by artists like Tawaraya Sotatsu and Ogata Korin. Unlike earlier large-scale paintings of flowering trees, Rimpa painters often focused on flowering plants, shown decoratively across folding screens, fans, and lacquerware.

Their paintings emphasized the most beautiful face of flowers: chrysanthemums, irises, lilies, and maples are often shown full-front, with unnecessary leaves or stems omitted. The effect is both natural and decorative — capturing the spirit of the plant while arranging it into a picture-like design.

In 1960, the Third Headmaster of the Ohara School, Houn Ohara, introduced Rimpa-cho Ikebana (“ikebana in the style of Rimpa”). He recognized the parallel between Rimpa paintings and ikebana: both capture the essence of plants through abbreviation and exaggeration.

Rimpa-cho arrangements are not bound by set forms like moribana or heika. Instead, they emphasize:

During his demonstration, Kamo-sensei placed two rectangular containers side by side, then threaded the gold-painted mulberry branches between them. This created a sweeping, unified line across the arrangement, much like the flowing movement of a Rimpa screen painting.

Clusters of chrysanthemums and lilies filled the containers, with red maple leaves scattered like brushstrokes. The eye was drawn across the two vessels as if reading a painted scroll — a living picture in flowers.

For many of us in the room, this was the first time seeing Rimpa-cho in person, or watching an arrangement span across multiple containers. The effect was striking: ikebana transformed into a painting in three dimensions.

Rimpa-cho connects us not only to the Ohara School but also to Japan’s broader artistic heritage. Next time you see a Rimpa painting — perhaps chrysanthemums scattered across a golden folding screen — imagine how those same flowers could bloom again in Ohara ikebana.

Joe Rotella

Associate Second Term Master

Ohara School of Ikebana